If I’m honest, my favourite read of the year was Yellow & Black by Konrad Marshall, a true inside story of how (my) team Richmond brushed aside 37 years of misery to win the grand final in the Australian Football League. There is not a skerrick of foreign policy in this richly reported book, unless you count a chance the Tigers will play in India sometime in 2018. And full-disclosure - I get a thank-you in the acknowledgements, and my real motivation in raising the book is that I can’t resist the urge to brag in the face of ridicule, having predicted Richmond’s success in a front page article in March.

If I’m honest, my favourite read of the year was Yellow & Black by Konrad Marshall, a true inside story of how (my) team Richmond brushed aside 37 years of misery to win the grand final in the Australian Football League. There is not a skerrick of foreign policy in this richly reported book, unless you count a chance the Tigers will play in India sometime in 2018. And full-disclosure - I get a thank-you in the acknowledgements, and my real motivation in raising the book is that I can’t resist the urge to brag in the face of ridicule, having predicted Richmond’s success in a front page article in March.

But to the wider world.

A savage warning by Russian journalist Alexey Kovalev was my highlight. Kovalev wrote ‘A message to my doomed colleagues in the American media’ just after Donald Trump gave his first press conference in January as the soon-to-be US president. This wasn’t a riff on the Russian influence story, but actually something darker. Kovalev recognised that Trump has changed reporting with an authoritarian turn - that facts can be neutered by bluster and the ‘gotcha’ stories that killed many a political career will matter no more.

It’s much worse. For all the conspiracy talk of ‘the media’ as if a single-minded behemoth, Kovalev acknowledged the lonely nature of the reporting profession. ‘If your question is stonewalled/mocked down/ignored, don’t expect a rival publication to pick up the banner and follow up on your behalf,’ he warned. Truth matters less than access.

This man owns you. He understands perfectly well that he is the news. You can’t ignore him. You’re always playing by his rules - which he can change at any time without any notice.

Kovalev’s essay – along with complaints by media academics such as Jay Rosen about attempts to normalise Trump - serve as true explainers for ‘fake news’.

Which is precisely what someone called my Tigers prediction on page 1 … Ha!

This is a book by a real international lawyer, but is much more than a book about international law. It’s a fast-paced detective story, researched with incredible depth, discovering the lives, roles, and sometimes tragic deaths, of a diverse cast of characters – Jews, Nazis, gentiles, children, parents, grandparents, orphans – before, during, and after the Second World War.

This is a book by a real international lawyer, but is much more than a book about international law. It’s a fast-paced detective story, researched with incredible depth, discovering the lives, roles, and sometimes tragic deaths, of a diverse cast of characters – Jews, Nazis, gentiles, children, parents, grandparents, orphans – before, during, and after the Second World War.

When I lived in Japan I was fascinated by the way internet tycoon Masayoshi Son broke through the bamboo ceiling that limits the citizenship rights of ethnic Koreans despite their residence in Japan for generations. And I always took visitors to a pachinko (gambling) parlour if for nothing else than the amazing aural experience. But I still didn’t understand this nether world.

When I lived in Japan I was fascinated by the way internet tycoon Masayoshi Son broke through the bamboo ceiling that limits the citizenship rights of ethnic Koreans despite their residence in Japan for generations. And I always took visitors to a pachinko (gambling) parlour if for nothing else than the amazing aural experience. But I still didn’t understand this nether world.

I’m watching the Ken Burns/Lynn Novich documentary

I’m watching the Ken Burns/Lynn Novich documentary

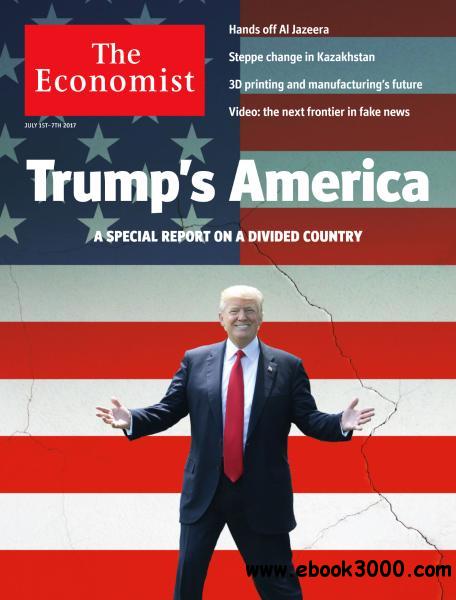

There was only one piece of reading in 2017 that led me to silently applaud at the end of it - The Economist’s

There was only one piece of reading in 2017 that led me to silently applaud at the end of it - The Economist’s

A rare bright spot in a sobering 2017 was the election in France of a young new president. I was relieved by Emmanuel Macron’s victory over Marine Le Pen, but I was also impressed by the scale of his political achievement. By sheer strength of will, Macron turned French politics upside down. His campaign for the Elysée was marked by energy and optimism. It was quite something to see him stride through the courtyard of the Louvre to deliver his victory speech to the strains of ‘Ode to Joy’, the European anthem.

A rare bright spot in a sobering 2017 was the election in France of a young new president. I was relieved by Emmanuel Macron’s victory over Marine Le Pen, but I was also impressed by the scale of his political achievement. By sheer strength of will, Macron turned French politics upside down. His campaign for the Elysée was marked by energy and optimism. It was quite something to see him stride through the courtyard of the Louvre to deliver his victory speech to the strains of ‘Ode to Joy’, the European anthem.

Making sense of populism has been a favourite theme of non-fiction writers in 2017, as they seek to rationalise the apparent collapse of a harmonious era of liberal, technocratic centrism. Provocative and powerful, Pankaj Mishra’s Age of Anger

Making sense of populism has been a favourite theme of non-fiction writers in 2017, as they seek to rationalise the apparent collapse of a harmonious era of liberal, technocratic centrism. Provocative and powerful, Pankaj Mishra’s Age of Anger